|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SECTION 12 THE INCREDIBLE JOURNEY OF CAPTAIN JOHN FRANKLIN TO THE SHORES OF THE POLAR SEA. 1819-22

The second* journey into Arctic waters by Franklin was conceived as a small overland expedition. Part of Secretary of the Admiralty, Sir John Barrow’s grand plan and insatiable desire for the mapping and charting of the North American Arctic coastline, was to explore the section eastward from the Coppermine River to Hudson Bay, a considerable unknown stretch of roughly 770 miles (1240 kilometres).

Command of an overland expedition timed to coincide with Lieut. Edward Parry’s voyage (see Sect 11) was given by the Admiralty to the then 33-year-old and much experienced explorer from Spilsby, Lincolnshire – the affable Lieutenant John Franklin. Partially in compensation for the fact that he had been thwarted by heavy ice in an 1818 attempt to reach the north-pole by the Spitzbergen route (as second-in-command with Captain David Buchan).

After consulting with the elderly Sir Alexander Mackenzie, (see Section 8) and receiving much useful information and promises of support from both the North West Company and Hudson's Bay Company, Franklin left London on the 23rd. of May 1819 on board the H.B.C. vessel Prince of Wales. He was accompanied by three officers, Dr. John Richardson, 24 year old midshipmen George Back and Robert Hood, both of the latter received promotion to Lieutenant for their conduct on this expedition. Franklin being promoted to Captain and Ordinary Seaman John Hepburn promoted to Able Seaman,(later second Master). Also on board were German settlers, bound for the Red River. The ship was initially escorted by the Eddystone, Wear and Harmony, the last being a Moravian mission vessel.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

That the Royal Navy actually expected their Naval officers, with no previous experience or special training, to complete an arduous, overland, military-style expedition of thousands of miles through unexplored territory, shunning the proven beneficial use of dog teams and choosing instead the method of man-hauling the under victualled supplies, were great expectations indeed; that they succeeded in large measure, was well-nigh incredible.

The expedition was victualled, equipped and ready to depart York Factory on 9th. of September 1819. Hudson‘s Bay Company servants, as well as a group of North West Company prisoners (aggressive rivalry between the two trading companies being then at its height), advised Franklin to winter at Cumberland House some 690 miles distant. The expedition arrived there on 22 October, having traced the well-known, if not previously well-mapped, route followed by the H.B.C., N.W.Co. and Indians alike. During that first winter at Cumberland House on the Saskatchewan River, Hood assisted the renowned surgeon-naturalist Dr. John Richardson in making natural history observations. All officers made important contributions to anthropology, climatology, and terrestrial magnetism. Hood however, was the first to prove that the action of the Aurora Borealis is an electrical phenomenon. Hood also painted North American Indians, mammals, and birds including four species that had not then been described to science.

Among other H.B.C posts, where they received considerable hospitality and supplies, they passed Norway House, founded by settlers fleeing from the Pemmican War. (see sect. 9) Most of the Cree Indians they met en route were in a sorry state, their circumstances and numbers having been reduced by the recent ravages of the killer virus measles and infectious whooping cough.

On 18th. January 1820 Franklin, Back and stalwart Orkney seaman John Hepburn left on an excursion to Fort Chipewyan some 857 miles away, walking for the most part on snowshoes and accompanied by two dog teams and two carioles to transport their provisions. The latter were supplied by both the H.B.C. and N.W.Co. following a certain amount of pressure to honour their promise of supplies. They followed the North Branch of the Saskatchewan River through the territory of the Stone Indians via Carleton House, and then northwest to the H.B.C. and N.W.Co. posts at Ile à-la-Crosse (the name being derived from the annual assembly point of the Cree Indians to play lacrosse), and thence, on through the Chipewyan territory, riding their carioles along the frozen rivers. At the N.W.Co. post Pierre au Calumet, (notable as the source of many a trader's clay pipe), they met John Stuart, the N.W.Co. explorer who had twice traversed the continent and reached the Pacific Ocean via the Columbia River.

The 25th. March announced the arrival of the expedition party at the N.W.Co.'s Fort Chipewyan on Lake Athabasca, having endured the annoying swarms of biting insects, where they remained until spring, gathering intelligence but few of the promised supplies from both the N.W.Co. and the nearby H.B.C. Fort Wedderburn, due to their fur-trade rivalries (see Pemmican War sect. 9). Much information as to the topography north of the Great Slave Lake was also garnered from visiting Indians, who along with certain voyageurs in the employ and secrecy of the fur trading companies, had travelled the northern waterways and terrain for years but this was the first time that a formal scientific expedition had set out to map the area since Hearne and Mackenzie. By 13th. July they have been rejoined by Richardson and Hood, who had elected to come up the Saskatchewan and Churchill (English) River route by canoe, ferrying the expedition’s much-needed supplies for the northern journey. During the voyage they had lost a foreman to drowning at Otter Portage.

The expedition thus re-equipped, departed Fort Chipewyan on 18th. July in three canoes containing the twenty-four men and their supplies, but very little food owing to the scarcity of meat and pemmican procured by Indian hunters who's numbers had been decimated by the widespread epidemic. Nevertheless, the N.W.Co.'s Fort Providence was reached without incident, despite the voracious mosquitoes. At Fort Providence (established 1789 and site of today's Yellowknife), the main expedition party was enlarged to thirty-one, including company voyageurs, two women and three children. Amongst its members were Frederick Willard Wentzell, District Clerk of the North West Company. Also accompanying the party were a number of Copper Indians as hunters and guides, including their Chief Akaitcho (Bigfoot), and guide Keskarrah. The former promising to lay in enough food to sustain the expedition down the Coppermine River.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Thus it was, that the entire expedition proceeded by a previously unexplored route via the Yellowknife River towards the Coppermine River, arriving at Winter Lake some 1,520 miles distant from York Factory by 20th. August, in eighteen days. It was there, that the construction of Fort Enterprise was commenced, which was to be the expedition's base for the next ten months.

While the fort was under construction and taking advantage of the mild weather prior to the onset of winter, the principal officers made two separate reconnoiters of the previously unmapped boreal terrain between Winter Lake and the Coppermine River, during the latter part of August and early September. By 6th. October, the fort was ready for occupation.

Meanwhile, Parry and Liddon in the 'Hecla' and 'Griper', unbeknownst to the expedition members was also over-wintering a mere seven hundred and twenty-five miles to the north. (See Sect. 11)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Back, Wenzel and six others set out on snowshoes for Fort Providence in order to bring up more supplies for the following year's exploration and to collect the mail newly arrived from England (which arrived at Fort Chipewyan during January 1821, along with two Eskimo interpreters). Not being satisfied with their reception by the H.B.C. Factor nor with the quantity of supplies at Fort Providence, Back and two others returned to Fort Chipewyan by snowshoe in an astonishing 10 days. They returned thence to Fort Enterprise, each carrying up to 90lb. back-packs of much-needed supplies by 17th. March. (rarely was a cause for celebration so apt on that St. Patrick's Day 1821). The journey comprised a round-trip trip of 1,104 miles, in the deep snow and treacherous ice of winter, sleeping in the open, with only a deerskin blanket, at - 40°F below : Hardy men indeed!

In his journal, Back kept meticulous observations regarding relations with the local Indian bands, learning much of their ways and traditions, the advantages and pitfalls of dog sleds, and remarks upon the Aurora Borealis.

Similarly, Franklin and the other officers had been keeping useful and keen observations of all that they saw during their over-winter sojourn, when detailed observations of geology and meteorology were made. The lowest temperature recorded being -57°F (-50°C). Much time was spent in the writing of journals, recording observations on the Native Indian culture, compiling of drawings and maps, along with considerable dalliance with the native women. Further observation was made of the elaborate construction of large multi-roomed snow houses /igloos, migration of birds, fish, flora & fauna, interaction and social structure of Indian bands, their winter preparations, trading expectations, provisioning and impact of the H.B.C. & N.W.Co. upon the native culture. Together with remarks on company traders, their assistance, attitude toward each other and expedition members.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The first party, under Dr. Richardson, left for Point Lake on the 4th. June 1821 with Franklin and the remainder of the expedition following on the 14th. Plagued by a bitter wind chill, then by the miasma of mosquitoes and the vacillations of the Indians, the reunited expedition members were again dangerously low on food, supplies and ammunition, after dragging canoes and baggage over 117 miles of snow and ice to their Point Lake rendezvous. Thus it came about, that they embarked the laden, if somewhat battered, open canoes for the perilous journey down the Coppermine River to the Hyperborean Sea, despite the virtual lack of knowledge as to the rapids and considerable drift ice. Upon arrival the Longitude & Latitude of Hearne’s position was then corrected. En route they passed with trepidation the scene of the Eskimo massacre witnessed by Hearne in 1771, (see section 2) travelling in all a distance of 334 miles from Fort Enterprise.

On 19th. June, at the mouth of the river, as arranged, Wenzel departed with the Indians, while Franklin and his party of 19 others set out across the unknown Arctic Ocean in two birch bark canoes with enough pemmican to last only 15 days. Coasting with the canoes under sail, they made good progress with remarkably little peril, distributing names of friends and colleagues to various landmarks as they went. They traversed Coronation Gulf, Bathurst Inlet and Melville Sound, making approximately 20 to 30 miles per day, but with signs of winter setting in, and being extremely low on pemmican, Franklin prudently decided to return for home before it became too late.

Meticulously charting their voyage, they were hoping to reach Repulse Bay which due to miscalculation of the position (Middleton not having the knowledge nor means to determine Longitude.) was 770 miles (1,240 Km.) to the east, by direct line, considerably further than Franklin estimated. His maritime voyage had already traced the deeply indented coast for 555 miles, but only 450 in direct line.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The return journey, however, was quite another matter. After a nightmare passage through heavy seas in the open birch-bark canoes, they made for the Hood River, erecting at its embouchure a post with information regarding the expedition for Parry (early charts which show this as the Coppermine River mouth - an intended landfall should Parry be successful). At Wilberforce Falls the larger canoes where were reconstructed as two smaller, more portable ones for the arduous 150-mile trek to Point Lake. Each man was expected, despite the lack of proper boots, to walk the distance carrying a 90 pound pack in unbelievable conditions across the Barren Lands, and even when they did stop to rest, their circumstances were no better: "As we had nothing to eat, and were destitute of the means of making a fire, we remained in our beds all the day; but the covering of our blankets was insufficient to prevent us from feeling the severity of the frost, and suffering inconvenience from the drifting of the snow into our tents. There was no abatement of the snow next day; our tents were completely frozen… Our suffering from cold in a comfortless canvas tent in such weather, with the temperature 20°F and without fire will easily be imagined; it was however, less than that which we felt from hunger ".

With fatigue and declining health, due to the inadequacies of their diet, (they must have had cast iron stomachs given what they could glean to survive on, but at the price of severe diarrhoea) rapidly overtaking the expedition, discipline was also breaking down. As if footslogging over very difficult terrain in the heavy snow and relentless cold of an early Canadian winter was not enough, the officers had to contend with the deceit of the perfidious Canadian voyagers. While skirting Contwoyto Lake, Franklin lost his valuable journal and meticulously kept observation notes in a canoe accident. On 23rd. of September, with fishing nets abandoned by an uncaring voyager, pemmican long finished and no Tripe-de-Roche (Rock Tripe edible fungus) to be found, they were forced to eat their shoes, scraps of leather from a pair of trousers, old deer skins, antlers and some old bones they found. Two days later, the men were looking death in the eye; only determination and accurate bearings kept them going. Having reached the Coppermine River again, with the canoes abandoned, they were barely able to cross, being so weak.

Franklin's personal discipline and sense of moral responsibility asserted itself to enable him to overcome the inadequacies of his naval training, which had not prepared him and his fellow officers to live off the land. This serious failing is encapsulated in the contempt shown for "gentlemen explorers" in the words of Sir George Simpson, then governor of the H.B.C.: “Lt. Franklin… Has not the physical power required… He must have three meals per diem. Tea is indispensable, and with the upmost exertion he cannot walk above eight miles in one day " a singular, unfair and inaccurate assessment of the man. However, the point was meant to show up at the inadequacies of officer training. Nonetheless, time and time again the products of British public schools and military and naval academies showed they could cut it.

In an attempt to save his men, Franklin and four others parted from the main group and struggled on to Fort Enterprise, only to find it devoid of the promised, much needed supplies. In a desperate attempt to secure provisions for the rest, Back showing true grit, and some others had already set off in advance of Franklin toward Fort Providence, hoping to meet up with some Indians en route, in order that at least some of the lives of the expedition members could be saved. Meanwhile, Richardson and Hepburn rejoined the skeletal survivors at Fort Enterprise, the party having been without meat or proper food for 31 days. They brought the gruesome news of cannibalism of two of the party and the murder of Lieutenant Hood by one of the four Indian voyageurs, Michel Terohaute, whom Richardson had subsequently executed, fearing for his own and Hepburn's safety.

One cannot imagine the disappointment of the expedition survivors upon observing the emaciated state of their companions and the dilapidated state of their base camp. Although very near to death, they managed to survive until the 7th. of November when humanitarian relief arrived from Chief Akaitcho’s camp, having been sent by Back, who had experienced a particularly harrowing and grueling journey. Thus, they were spared, and eventually made their way to Fort Providence and from there, reunited with Back, and with health restored, they returned to York Factory on 14th. July 1822 after their round-trip of 5,550 miles. From there they returned to London.

During their recuperative sojourn at York Factory, they met the Reverend John West of the Church Missionary Society, the first protestant missionary to the shores of Hudson Bay. West later travelled to the Red River Settlement and Churchill, where he established mission posts among the Eskimos.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The expected assistance from the both the fur trading companies then at the height of the ‘pemmican’ fur trade war, (which resulted in the amalgamation of the two companies in late 1821) and native peoples was less forthcoming than expected. The dysfunctional supply line due to the epidemic sweeping the first nations, coupled with unusually harsh weather and the resulting absence of game, meant the explorers were never far from starvation.

True, the expedition was plagued by unreliable allies and bad luck, indicating a certain degree of poor planning and considerable inability to adapt to living off the frozen land, but Franklin was a sailor, not a landsman. Hindsight, however, is always 20/20. Lt. Franklin and his excellent choice of hardy officers cannot be faulted for their determination to execute their orders for the exploration and charting of a portion of Northern Canadian coastline and accurate mapping of the course of the Yellowknife, Coppermine & Hood Rivers. Back in England he was considered a hero in the eyes of public opinion and in folklore “the man who ate his boots.”

One perhaps might question Barrow’s wisdom of a naval overland expedition, but his officers executed their orders to the highest degree, enhancing the spirit of great Royal Naval tradition.

An interesting comparison can be drawn between the journeys of Hearne and Franklin (and later explorers, such as Rae) in their attitudes toward the Barren Grounds. Hearne and Rea being accustomed to "off the land" survival techniques, found it a considerably less barren place than did Franklin, who due to his rigid training and despite some technologically - advanced equipment, was desperately ill-equipped with regard to survival clothes and techniques. Franklin trusted to supplies man-hauled along, rather than to clothing, hunting and survival skills perfected by local natives over the centuries. This failure to adapt, coupled with British ethnocentricity, spurred on by a sense of military or naval duty and the visions of men like Barrow, placed expedition members in what was perceived as an inhospitable and deserted landscape, thus compromising their lives. Eleven of the twenty member expedition perished. Natives and fur traders, on the other hand, with their less myopic attitude, managed to live in the same environment quite successfully. The illusion that official British expedition members gave their lives for the greater glory of Empire and quest for geographical knowledge is presumptuous indeed, when with a more enlightened attitude toward survival training, the environment and its native peoples, more knowledge could have been gained both sooner and at less cost.

If Simpson was correct, why did Franklin, Richardson, Back & Hepburn willingly accept service to further the cause of British geographical exploration on a number of subsequent voyages to the same inhospitable part of the world? There was, undoubtedly the significant incentive of Naval career advancement, promotion at a time of post Napoleonic war recession. Regardless, it required a very special kind of officer to travel to the far corners of the earth to further Britain’s exploration of some of terrestrial earth’s final frontiers and officers from all corners of the British Empire answered that call.

Nevertheless, Franklin’s journal truly tells a tale of hardihood, endurance and the courage of his companions, to ‘stir the heart of every Englishman” (to paraphrase R.F. Scott). He and his officers, with the exception of the luckless Hood, survived - just - their incredible journey.

*Although actually his second voyage into Arctic waters, this journey has become generally known as Franklin's First expedition/voyage.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

References cited or consulted:

Franklin, Capt. John. Narrative of a Journey to the shores of the Polar Sea in the years 1819, 20, 21 and 22. London 1823,

The Journal and Paintings of Robert Hood, Midshipman with Franklin. Montreal: McGill-Quccn’s University Press.

Lande, L. The Lawrence Lande Collection of Canadiana in the Redpath Library at McGill University - A bibliography. Montreal 1965

Lopez, B. Arctic Dreams C. Scribner's sons, New York 1896.

Sabin, J. Bibliotheca Americana, A Dictionary of Books relating to America. New York 1868-1936

Cartographica. Explorers maps of the Canadian Arctic 1818-1860. Monograph No 6. York University, Toronto 1972.

Cooke, Alan & Holland, Clive. The Exploration of Northern Canada 500-1920 A chronology. The Arctic History Press, Toronto 1978

Mountfield, D. A History of Polar Exploration Dial Press New York 1974

Tooley Dict. Tooley, R.V. Tooley’s Dictionary of Mapmakers New York 1979

Kerr, D.G.G. A Historical Atlas of Canada. Toronto 1960

Harris, R. Cole Historical Atlas of Canada Vol I. University of Toronto Press 1987

Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coppermine_expedition

Britain’s small Forgotten Wars: http://www.britainssmallwars.co.uk/the-franklin-coppermine-expedition-north-east-canada-1819-22.html

Dictionary of Canadian Biography: http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hood_robert_6E.html

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

It is from Franklin’s published Narrative of a Journey to the shores of the Polar Sea in the years 1819, 20, 21 and 22. London 1823, that the following are extracted:

UNLISTED STATE OF TWO IMPORTANT EXPLORATION MAPS

FRANKLIN, HOOD & OTHERS - North Central Canada.

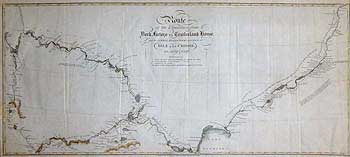

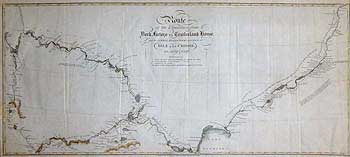

ROUTE/ of the Expedition from/ YORK FACTORY to CUMBERLAND HOUSE/ and the SUMMER & WINTER TRACKS from thence to/ ISLE A LA CROSSE, / in 1818 & 1820.

CAPTAIN JOHN FRANKLIN, ROBERT HOOD & OTHERS

State II Hand-tinted John Murray, London Nov. 1823

Printed on thin wove paper 9 ¾ x 21 5/8” (24.7 x55 cm.)

Ref. LRAm 803/DRL/a.dosa>RSL

Published in the second edition of Franklin's Narrative, this second state of the map is identical to the first, apart from the imprint November 1823. Engraved by John Walker, the fine detail has been enhanced by delicate hand tinting.

This map details the first part of the expedition’s epic journey from York Factory (Hudson’s Bay) to their first winter headquarters at the H.B.C.’s Cumberland House. The tracks of Hood’s excursion (23rd. of March to first week in April 1820) in order to draw a moose, the first leg of Franklin and Back’s 857-mile snowshoe trek via Fort Isle à la Cross (Saskatchewan) are also indicated, along with the route of Dr. Richardson and Hood’s month-long canoe journey of June/July 1820 to join Franklin with the supplies.

The map is filled with fascinating information with regard to topography and geology. Portages, Native iconography, H.B.C. and N.W.Co. posts, scientific and other observations are noted along the expedition route.

Cartographica 6 does not list this second state of the map; their State II is in fact, a third state.

Vide: Clements, Vol2. p.495

Sabin 25624

Compare: Cartographica #6, Map 20

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CAPTAIN JOHN FRANKLIN, ROBERT HOOD & OTHERS

State II Hand-tinted John Murray, London, Nov.1823

Printed on thin wove paper 20 x 9” (51.3 x 23 cm.)

Ref. LRAm 802/DRL/a.dosa>ALN

This is a continuation of the previous map, showing the progress of the expedition to beyond Slave Lake (Alberta). As with its companion, this delicately hand-tinted map is filled with scientific detail. In his “Narrative”, Franklin states that the map of their progress was compiled each evening by Lieut. Hood, incorporating the exacting survey and the many scientific observations as to geological, meteorological, magnetic, botanical, native, topographical and zoological sightings made en route. Notes were also made as to the appearance of the Aurora Borealis. Following Hood’s murder, the work was continued by the other officers, the information being eventually set down on these maps by Franklin and engraved by J. Walker. Again, Cartographica 6 does not list this second state.

Vide: Clements, Vol2. p.495

Sabin 25624

Compare: Cartographica #6, Map 21

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

FRANKLIN, HOOD & OTHERS - Northern and Arctic Canada.

A CHART/ of the/ DISCOVERIES & ROUTE/ of the NORTHERN LAND EXPEDITION, /under the command of CAPTAIN FRANKLIN, R.N. / in the years in 1820 & 21.

CAPTAIN JOHN FRANKLIN, ROBERT HOOD & OTHERS

State I Hand-tinted John Murray, London, March 1823

Printed on thin wove paper, some age spotting, small chip center below lower border. 32 x 19” (81.4 x 48 cm)

Ref. LRAm939/GN/da.dosa>LNN

This is the finest copy of this important Canadian Arctic map that we have yet seen, handsomely embellished with delicate hand-tinting. The first state, bearing the imprint ‘March 1823’ and engraved by J. Walker. As with the above, it delineates the progress of the expedition, from Great Slave Lake down the Coppermine River to Melville Sound and is filled with a wealth of scientific and topographical detail.

The expedition averaged 6 to 12 miles per day by foot, or 15 to 25 miles by canoe, and their tracks are shown to their second winter base at Fort Enterprise, completing the 1,520 mile first leg from York Factory. Their fall reconnoiters to Point Lake are shown, as well as the summer descent of the Coppermine River, which corrected Samuel Hearne’s reckoning of its exit to the ocean by nearly 200 miles to the east. This new information fuelled the case of Alexander Dalrymple (chief cartographer to the East India Company and first Hydrographer to the Admiralty-see section 9) for a North-West passage from Hudson Bay to the West Coast. When he accurately calculated that Hearne had inadvertently also placed the mouth of the river 200 miles too far north, he then speculated that a passage might still lie north of 67° 48’ but south of 70°.

The impressive feat of accurately charting some 555 miles of previously unknown coastline during their astonishing arctic ocean voyage in open canoes is delineated, as is the harrowing return journey up the Hood River, and thence, with starvation setting in, across the Barren Lands via Congeca-tha-wha-chaga (Kathawachaga) Lake. The inaccuracies of Hearne’s survey in locating the lake further west caused Franklin much delay and grief.

Had he known of the error, Franklin states that he would have kept further west himself, thereby saving several punishing days march.

Contd. below....

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

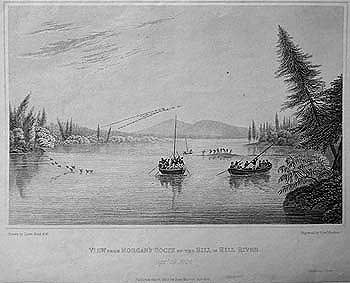

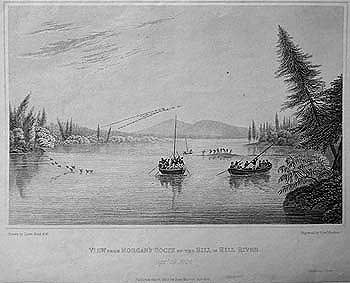

VIEW From MORGAN’S ROCKS of the HILL in HILL RIVER Sept. 19, 1819.

Uncoloured

Size 6 ¾ x 8” (17.2 x 20.5cm.)

Ref. LRAp 595a/G.LN/l.dosd>VL

Having travelled only one and three-quarter miles on September 19th. due to hauling the boats over several rapids, most of the expedition members are seen in this view, note that the boats are being poled along the Hill River as opposed to rowing. The expedition encamped on the flat rocks of the three-quarter mile wide river. The interior was "broken into a multitude of cone shaped hills”, the highest of which was 600 feet. From its summit, 36 lakes are said to be visible and "the beauty of the scenery, dressed in tints of autumn called forth our admiration and was the subject of Mr. Hood’s accurate pencil". Opp.p.33

THE TROUT FALL Sept.1819

Uncoloured, some browning due to age.

Size 6 ¾ x 8” (17.2 x 20.5cm.)

Ref. LRAp 595/G.LN/l.dosd>VL

“At the first of these portages the river falls between two rocks about sixteen feet, and it is necessary to launch the boat over a precipitous rocky bank… the rocks which form the bed of this river are slaty, and present sharp fragments by which the feet of the boatman are much lacerated ”. As is here aptly depicted, this was hard going indeed. It is no wonder that Franklin’s party decided to exchange the modified heavy York boats for the lighter (Ca.300 lbs.) Athabasca canoes upon reaching Fort Chipewyan. Interestingly some of the Indians they met along the route recalled having met Alexander Mackenzie (see section 8) and Samuel Hearne (see section 2). Opp.p.37

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

MANNER OF MAKING A RESTING PLACE ON A WINTER’S NIGHT. March 15. 1820

Original hand tinted aquatint.

6 ½ x 7 5/8” (16.5 x 19.4cm.)

Ref. LRAp 987/EN/da.dose> [ENN] not for sale

This splendid and atmospherical image appears in Franklin’s Journal opposite page 97, implying that the expedition was making a winter encampment amid the dense pine forest flanking the North Branch of the Saskatchewan River, however it is confusingly dated by the artist Back, March 15, 1820, It was on the night of the 14th. that the expedition was actually encamped among a cluster of fine pine trees, being a pleasant well sheltered place having travelled fourteen miles near the junction of the Pembina and Methye Rivers. The Journal’s accompanying map, however, puts them in that location on July 2nd.

Regardless of the precise date or location, the image affords a fairly detailed depiction of the manner of making a campsite. The bed of pine branches being spread to the right of the camp fire upon the cleared snow, upon which the blankets would be laid. Three sled dogs still attached to the customized sleds/carioles, snowshoes stuck upright in a snowbank or hung on a tree. Fire wood and pine branches being gathered by the voyageurs and supplies (up to 300 lbs. for each sled!), being hung out of dogs reach upon the pine branches. On many nights the temperature was so low that the mercury dropped into the bulb and froze. Opp.p.97

THIS ITEM IS NOT INCLUDED IN THE SALE OF THIS SECTION

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

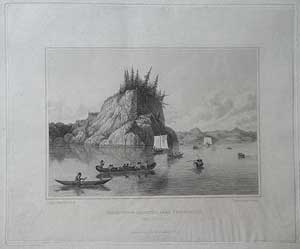

THE EXPEDITION DISCOVERING THE COPPERMINE RIVER Sept. 1, 1820.

Uncoloured, some browning due to age. Size 6 ¾ x 8” (17.2 x 20.5cm.)

Ref. LRAp 592/G.LN/o.dosl>VL

Having deposited their canoe, their guide being uncertain as to the water route, Hood and Back’s party then proceeded on foot, carrying their tents and supplies. The party reached the shores of Point Lake, through which the Coppermine River runs, on Sept 1st. The members of the expedition were the first Europeans to see the river since Hearne in the previous century. Having inspected the lake for alternative routes, the expedition returned thence to Fort Enterprise, a round trip of 110 miles, much of it in wet clothes, through fog, over rough and difficult terrain.

Opp.p.237

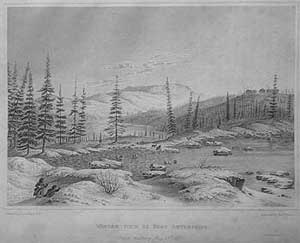

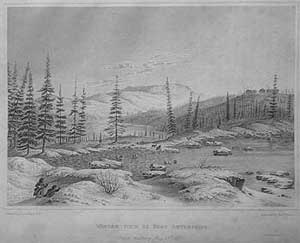

WINTER VIEW OF FORT ENTERPRIZE, [sic.] Snow melting May 13th. 1821

Uncoloured, some browning due to age. Size 6 ¾ x 8” (17.2 x 20.5cm.)

Ref. LRAp 589/G.LN/o.dosl>VL

“On the 6th. October the house being completed, we struck our tents and removed into it. It was merely a log building fifty feet long and twenty-four feet wide, divided into a hall, three bedrooms and a kitchen. The walls and roof were plastered with clay, the floor laid with planks rudely squared with a hatchet, and the windows closed with parchment of deerskin. The clay… froze as it was daubed on, afterwards cracking in such a manner as to admit the wind from every quarter." In the store house they laid in 100 deer, and 1000 pounds of suet dried meat (Pemmican). By the end of the month the men had completed their two-room 34’ x 18’ bunkhouse. These three buildings, together with some Indian tents, located in the shape of a quadrangle comprised Fort Enterprise, which is seen atop the hill to the right of this view. The day following the making of the drawing for this engraving by Back in 1821, the first robin was seen, heralding the return of warmer weather. About the same time, the geese and ducks reappeared. Living in such quarters for some ten months inevitably produced discord, particularly among the somewhat uncouth voyageurs. The discord was not confined to the voyageurs; the irascible Back and artistic Hood had fallen out over their rivalry for the affections of a 15-year-old First Nations Copper Indian girl nicknamed Greenstockings, and would have fought a duel with pistols over her, had John Hepburn not removed the gunpowder from their weapons. The situation was defused when Back was dispatched south. Hood subsequently fathered a daughter with Greenstockings.

Opp.p.246

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

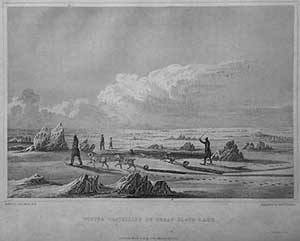

WINTER TRAVELLING ON GREAT SLAVE LAKE.

Uncoloured, some browning due to age. Size 6¾ x 8” (17.2 x 20.5cm.)

Ref. LRAp 591/G.LN/o.dosl>VL

On St. Patrick's Day 1821, that intrepid walker, Lieutenant George Back, returned to the winter fort after an absence of nearly five months, having walked in that time 1,104 miles in winter conditions to Fort Chipewyan (via Fort Providence) for supplies and to collect the mail for the main expedition party housed at Fort Enterprise. He travelled on snowshoes, with no other covering at night than a blanket and deerskin, with the thermometer frequently at -40°F (-40°C), and once at-57°F (-50°C), often going two to three days without food. Writing 199 years later, to the day, with the advantage of technological advances in clothing, freeze dried food, communications and all exploration since, this amazing feat of endurance seems all the more remarkable. The simplicity in relating of the events of Back’s journey is significant, for it could only have come from the pen of one who has experienced such deprivations and conditions. Back stated that on December 8-9 they crossed Great Slave Lake with an excessively cold northwest wind creating such an excruciating cold wind-chill that they had to run to keep themselves from freezing: a difficult task amidst the pressure ridges of lake ice congelation. It was so cold that two of the party had their faces and ears frozen almost immediately. The engraving depicts the incident in which some of the dogs in attempting to cross thin ice, fell into the water, from which they were saved only with difficulty: though escaping a frigid death they suffered dreadfully from the cold. This was the pioneering use of dogsleds by a British naval expedition. Despite centuries of use by Indians and Eskimos, the use of dog teams was constantly shunned by Royal Naval expeditions to both polar regions in favour of man-hauled sledges, even into the twentieth century. The expeditions of the few officer explorers who could see the obvious advantages of dog pulled sledges tended to be more successful.

Opp.p.277

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

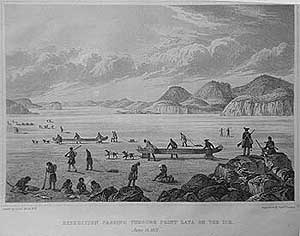

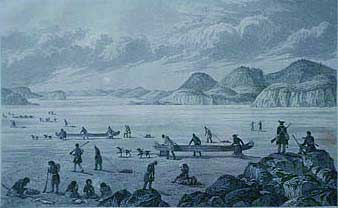

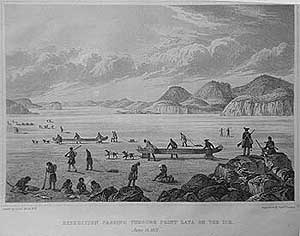

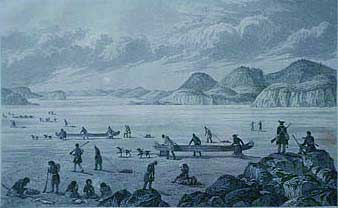

EXPEDITION PASSING THROUGH POINT LATA [sic.] ON THE ICE. June 25, 1821

STATE I Uncoloured, Size 6¾ x 8 1/8” (17.2 x 20.7cm.)

Ref. LRAp 794/DE.GN/a.dosr> DAL

This descriptive view accurately depicts the moment of setting off of the main expedition toward the Coppermine River and the Arctic Ocean: “June 25 [1821] – the wind having abated in the night, we prepared for starting at an early hour. The three canoes were mounted on sledges and nine men were appointed to conduct them, having the assistance of two dogs to each canoe. The stores and provisions were distributed equally among the rest of our men”p323. Each of the smaller sledges, containing 180 pounds, was man-hauled across the lake. The weather varied in the extreme, from snow, heavy rain, fog, and heat, leading to the exhaustion of the party. The surface of the ice, being honeycombed by the recent rains, presented innumerable sharp points, which tore our shoes, and lacerated the feet at every step. The poor dogs, too, marked their path with their blood. p.325. Their course led down the main channel of the lake, which varied from half a mile to three miles in breadth. "June 30 - the ice cracked under us at every step and the party were obliged to separate themselves widely to prevent accidents,… We landed at the first point we could approach… the evening was very warm, and the musquitoes [sic.]…Our distance today was six miles”p.326/7

This engraving bears the words ‘POINT LATA’ in the title, making it State one.

Opp.p.323

EXPEDITION PASSING THROUGH POINT LAKE ON THE ICE. June 25, 1821

STATE II Uncoloured, printed on India paper. small loss to top left border, not affecting image.

Size 6¾ x 8 1/16” (17.2 x 20.4 cm.) Ref. LRAp Arc62/DN/o.dosl> DAL

This is state two of the plate, being the large paper Deluxe Edition, printed on India paper and tipped onto a wove backing (12 x 171/8”) this deluxe printing was not bound into any additions of the Narrative.

The handsome engraved image contains a horizontal scratch on the foreground rock, on top of which stands an expedition officer (Franklin himself?) With the manuscript observations for his journal strapped across his back and servant John Hepburn by his side. All copies of states II and III examined contain this scratch. State II also has a vertical scratch in front of the leading figure beyond Franklin and the figure on the ice to the rear of the foreground canoe. Beneath the image the inscription regarding Shury, the printer does not appear

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

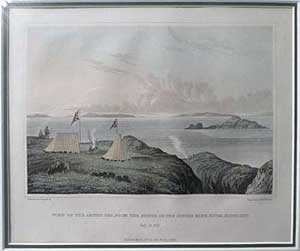

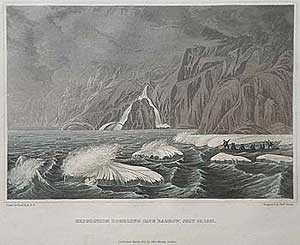

EXPEDITION DOUBLING CAPE BARROW July 25, 1821

Original hand tinted aquatint,

Size 6¾ x 7 5/8” (17.2 x 20 cm.)

Ref. LRAp 593/G.LN/l.dosd> DAL

If one announced today an expedition to traverse part of the Arctic Ocean at the extremity of an Arctic summer amid the ice flows, in open birchbark canoes, without any safety equipment or means of communication, and virtually without supplies or food, one would probably be locked away and classified unstable. Yet in 1821, that is what Franklin, and his men of sound mind and body, succeeded in doing - just. Putting their fate in the hands of God, (all the officers maintained strong religious faith) they sought a channel, between the different masses of gale force driven ice, which they fended off with poles to avoid being crushed. Back’s view of Cape Barrow named for the Admiralty Secretary whose exertions contributed much to Arctic geographical knowledge, depicts the peril of the situation and the dreariness of their prospect, in original colour as issued.

Opp. p.367

EXPEDITION ENCAMPED AT POINT TURNAGAIN Aug. 21, 1821

Uncoloured, some browning due to age.

Size 6¾ x 8 1/8” (17.2 x 20.7cm.)

Ref. LRAp 587 /G.LN/l.dosd>VL

The windswept Point Turnagain was the expedition’s final campsite on the Kent peninsula. The 555 miles of coast sailed to this point (indeed, Richardson, Franklin and Back walked 10 to 12 miles further along the coast toward the distant headland) proved to be a major stepping stone in the delineation of Canada's Arctic coastline. After taking as many observations as possible, they departed that desolate spot with "the utmost alacrity" on 22 August. The collective opinion of the officers, concerned that they could be trapped by the early onset of winter, persuaded them that departure was the prudent choice.

Opp. p.387

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

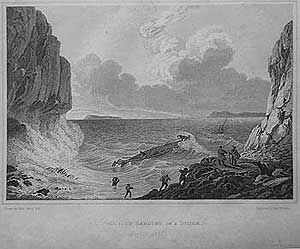

CANOE BROACHING INTO A GALE OF WIND AT SUNRISE Aug.23, 1821

Original hand tinted aquatint,

Size 6 ½ x 7 5/8” (16.5 x 20 cm.)

Ref. LRAp 593/G.LN/l.dosd> DAL

Our image bears the inscription “Drawn by Lieut. Hood RN" Subsequent printings bear the inscription “Drawn by Lieut. Back RN”. Yet another perilous situation is depicted, for to ‘broach to’ is always fraught with danger, as sailing vessels have a tendency to fly up into the wind. To make a 15-mile traverse in a light birchbark open canoe, across Melville Sound, before a strong wind and heavy sea, was taking a grave risk indeed: only the extreme deprivation of food which "absorbed every other terror", Franklin writes, gave them the courage to attempt it. Even so, it was with the upmost difficulty that the canoes were kept from turning their broadsides into the waves. This handsome aquatint is mute testament to any sailor who, in a small vessel, has faced the treachery of a heavy sea whipped up by gale force winds. This print bears the original hand tinted colour as issued.

Opp. p.394

EXPEDITION LANDING IN A STORM Aug.23, 1821.

Uncoloured, some browning due to age.

Size 6 7/8 x 8 1/8” (17.5 x 20.7cm.)

Ref. LRAp 584 /G.LN/l.dosd> VL

Having survived the open boat journey, the expedition discovered that landing was a different matter. The heavy surf threatened to dash them against the rocks; in the event, they had to run at an open beach and chance the waves, wading up to their chests to unload their meagre supplies. The second canoe split its head in the landing attempt but was later repaired. The danger of the landing is graphically captured in this engraving by Back.

Opp. p.395

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

WALKER - Northern Canada and Arctic Regions

An Outline to shew the CONNECTED DISCOVERIES of Captains Ross, Parry, & Franklin in the years 1818,19,20 and 21

J. Walker, engraver. London 1823

State II original outline colour, some strengthening along folds.

printed on thin wove paper 14 ¼ x 18” ( 36 x 45.5cm.)

Ref. LRAm 804/DSL/a.dosa>LNN

State II of the map with the same title, which appeared in Franklin's ‘Narrative…’, bears the imprint ‘Novr. 1823’ and differs considerably from State I, which bears the imprint ‘March 1823’. This State II map was published in the second edition London 1823, of Franklin’s ‘Narrative…’.

The map differs from State I in that an addition has been added to the original plate, creating a larger size map with numerous geographical changes. The map now extends south of the Columbia River in the west and to Quebec City and part of Nova Scotia in the east. In the northern Canadian interior, many more lakes have been added and named, also Great Slave Lake is fully delineated. The delineation of the west coast has been added. In the Arctic regions, the east coast of Greenland has been redrawn and place names added. As in State 1, two deltas of the Mackenzie and Coppermine Rivers are shown (being the first recorded and the second being the corrected re-position) with the shape of Southampton Island remaining unaltered.

This useful map, which uses the Arrowsmith map as a base, is coloured in blue outline, with the tracks of the Franklin expedition in red. It shows the extent of the northern and Arctic discovery at the beginning of the revival of interest in the north, during the commencement of George IV’s reign and the period of Napoleon's final exile on St. Helena following the European wars.

NOTE: this State of the map is NOT RECORDED IN CARTOGRAPHICA 6, #3 the States II and III listed there are yet other states and should be listed as States III and IV.

Vide: Sabin 25625

Compare: Cartographica #6, Map 18

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

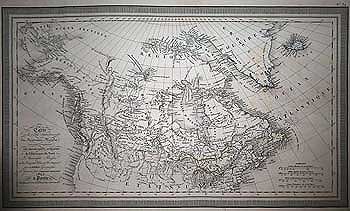

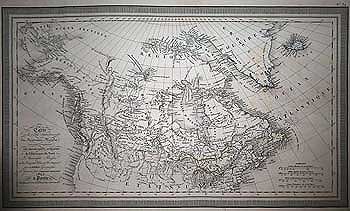

VIVIEN - British North America

CARTE de la Partie Septentrionale DU NOUVEAU MONDE; ou sont Compris LES POSSESSIONS ANGLAISES de l’Amérique du Nord…. Arctiquea.

Louis VIVIEN Paris 1825

Outline Colour

10 ½ x 17 7/8 (26.6 x 45.4)

Ref. LRAm1125/SL/r.dosg>LNN

The first edition of the map published in Louis Vivien St. Martin Atlas Universal Paris 1825. Engraved by Giraldon-Bovinet, Vivien’s map, which is based on that of Arrowsmith, shows by outline colour the vast limits of the H.B.C. controlled Rupert's land. Also delineated are Upper and Lower Canada, which were experiencing a settlement boom at this time, and the extent of westward American exploration, as well as the second wave of Russian exploration along the Alaskan coast. The British Columbia coast is named ‘Archipel de Quadra et Vancouver’ with the whole of Vancouver Island named ‘Nootka’. In Rupert's Land, which at this time comprised nearly 40% of modern Canada following the cessation of hostilities and the amalgamation of the N.W.Co. with the H.B.C. (1821), the mapped extent of the fur trader/surveyor explorations is here delineated with place names, topographical features and Indian trade areas given. In the Arctic, the results of the Ross, Franklin and Parry first expeditions are shown, but not those of Parry’s second. This is an uncommon map of Alaska, Canada and the Northwestern US, in the decade following publication of Lewis & Clark's seminal map of the Northwest. The engraved title is to the lower left, with four scale bars giving nautical, British, Russian and French distances. The whole is surrounded by an engraved geometrical design border. Louis Vivian de St. Martin 1802-1896 was a 19th. century French geographer based in Paris.

To purchase the original antique Maps and Prints of section 12 Contact us

© Darrell G. Leeson MMXX

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)